Princeton Theological Seminary was established in 1812, the first Seminary founded by the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church. The establishment of The Theological Seminary at Princeton marked a turning point in American theological education.

The College of New Jersey, later to become Princeton University, was supportive of this plan because they recognized that specialized training in theology required more attention than they could give.

With fewer than a dozen students, in 1812 Archibald Alexander was the first, and for one year the only, professor. He was joined the following year by a second professor, Samuel Miller, who came to Princeton from the pastorate of the Wall Street Church in New York.

The original “Design of the Seminary” noted that the purpose of the Seminary is:

to unite…piety of the heart…with solid learning; believing that religion without learning, or learning without religion, in the ministers of the gospel, must ultimately prove injurious to the church

So it was that Princeton Seminary deliberately defined itself as a school of “that piety of the heart,” a training center for church leaders of all sorts, which specialized in preaching, the cure of souls, evangelism, and missions.

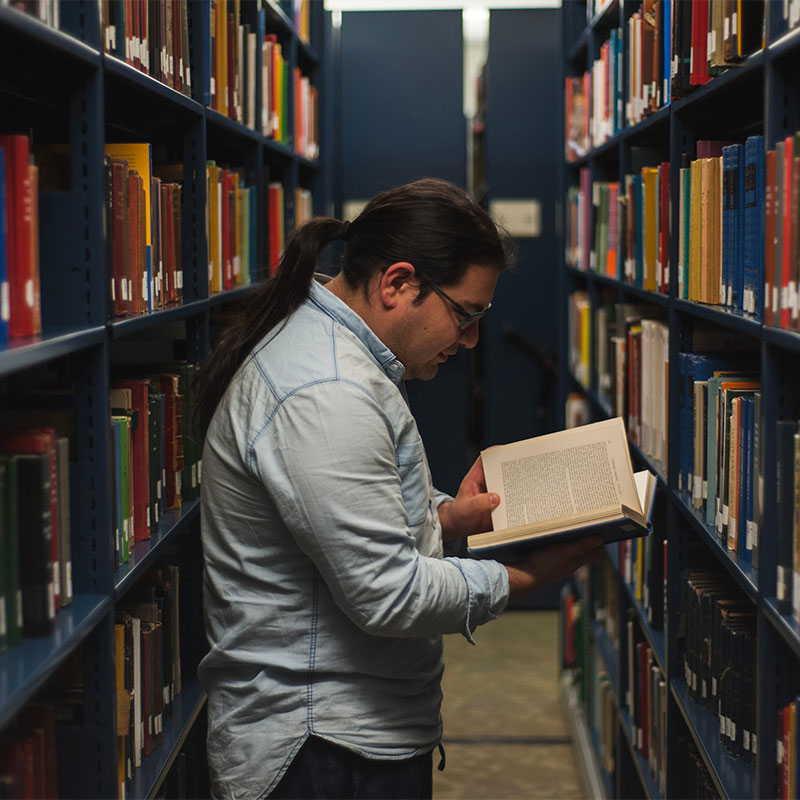

The other side of the piety-learning formula was equally important for the founders of the Seminary. The new institution was never described as a Protestant monastery or retreat, a place distinguished mainly for prayer and meditation. It was to be a school with teachers and students, library and books, ideas of the mind as well as convictions of the heart, all in the service of “solid learning.” The Reformed tradition, to which Princeton Seminary was and is committed, has always magnified intellectual integrity of the faith. Theology has been a highly respected word on the campus.

Affiliated from the beginning with the Presbyterian Church and the wider Reformed tradition, Princeton Theological Seminary is a denominational school with an ecumenical, interdenominational, and worldwide constituency. This is reflected in the faculty, in the curriculum of studies, and in the student body. The Seminary has been served by a remarkable succession of presidents:

- Francis Landey Patton (1902–1913) came to the Seminary after serving as president of Princeton University.

- J. Ross Stevenson (1914–1936) guided the Seminary through some turbulent years and expanded the institution’s vision and program.

- John A. Mackay (1936–1959) strengthened the faculty, enlarged the campus, and created a new ecumenical era for theological education.

- James I. McCord (1959–1983), whose presidency saw the institution of the first center of continuing education at a theological seminary, the establishment of full endowment for twenty-six faculty chairs, and the construction or renovation of major campus residences and academic facilities, gave leadership to both the national and world church through denominational and ecumenical councils.

- Thomas W. Gillespie (1983–2004) increased the size of the faculty, including the establishment of nine endowed chairs, and significantly lowered the student/faculty ratio.

- Iain R. Torrance (2004–2012) led a curriculum review and revision of the Master of Divinity degree program, and supported the use of new technologies in administrative and academic areas. Under his leadership, the Seminary initiated an Office of Multicultural Relations and the Board of Trustees initiated a major capital campaign to build a new library in service to the church in the world, and new campus apartments for student families.

- M. Craig Barnes (2013-2022) shepherded the Seminary through a period of transformation and community building, resulting in a greater racial, gender, and theological diversity in the faculty and student body. He led Princeton Seminary’s journey of confession and repentance of the school’s historical connections to slavery, which resulted in the 2018 report titled Princeton Seminary and Slavery and the establishment of an action plan with more than 20 initiatives designed to create a more inclusive culture at the Seminary. Academically, Princeton Seminary introduced the Farminary, a new curriculum, a revitalized PhD program, and two new degree programs during Barnes’ tenure as president. He also guided the Seminary through the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jonathan Lee Walton became the Seminary’s eighth president in January 2023. Prior to his appointment, he served as dean of Wake Forest University’s School of Divinity where he occupied the Presidential Chair in Religion & Society, and as the Plummer Professor of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in the Memorial Church at Harvard University. Dr. Walton is trained as a social ethicist whose scholarship focuses on the intersection of evangelical Christianity, mass media, and political culture. He is the author of two books and has published widely across various academic journals, books, magazines, and newspapers.

Learn more about the History of the Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary : a narrative history, 1812-1992

Princeton Seminary in American religion and culture